Why Our Name?

Modrý Robota draws from the Czech word robota, meaning forced labor or servitude—the etymological root of our modern word "robot." When Karel Čapek introduced "robot" in his 1920 play R.U.R., he wasn't simply naming a machine; he was invoking centuries of human bondage, transforming ancient systems of exploitation into gleaming new forms. The robota was the labourer who existed to serve, and in our name, becomes tinged with the melancholy blue of alienation.

In correct Czech, it would be modrá robota—"blue forced labor/slavery." Our deliberate use of the masculine modrý creates a grammatical impossibility, a linguistic tension that mirrors what we attempt to grasp: the simultaneous existence of both machine and human bondage, two sides of the same coin in our evolving economic landscape. This deliberate tension reflects our approach to analyzing systems—recognizing contradictions rather than smoothing them over.

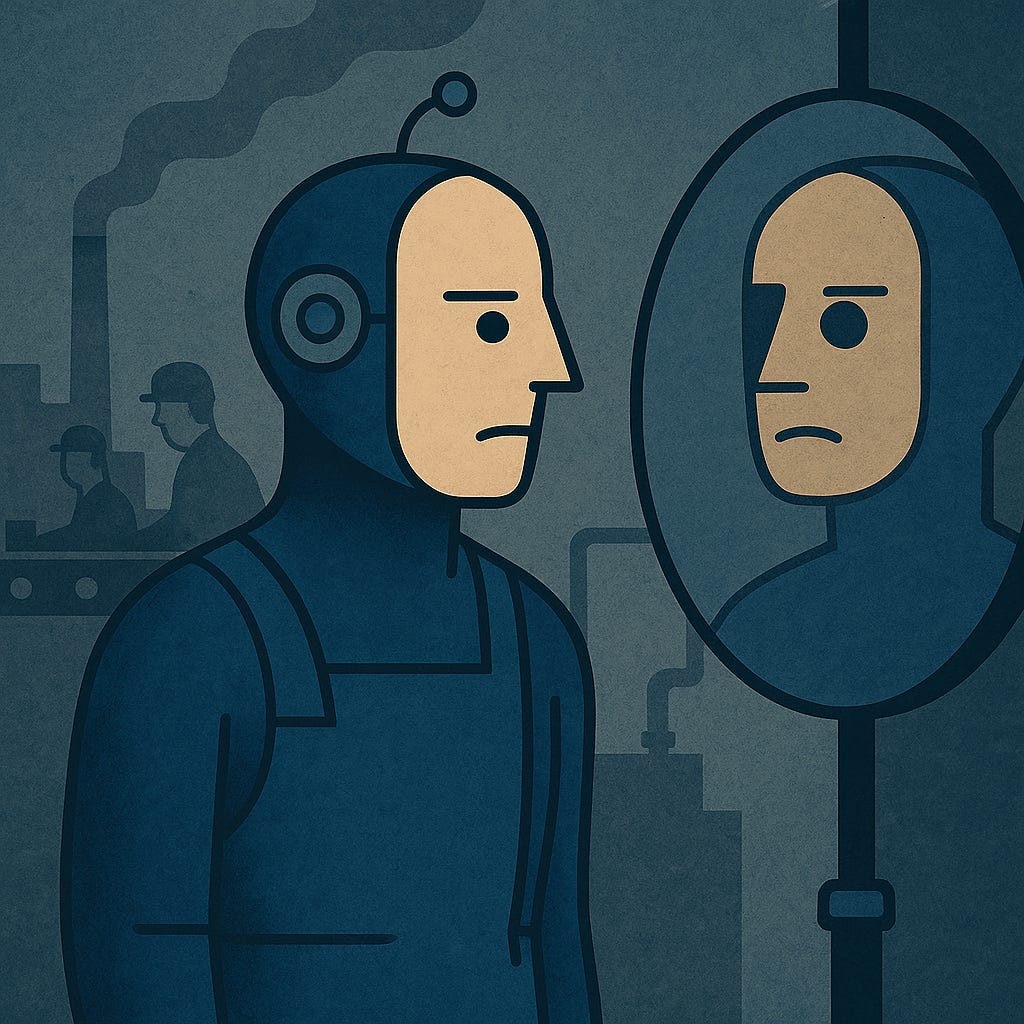

Contemporary capitalism positions both humans and cognitive machines in parallel relation to production—as resources to be optimized, inputs whose worth is determined solely by what they can produce. The worker who must sell their labor to survive and the machine designed to serve without rest share a fundamental condition: both exist primarily as instruments of production, both generate value that flows elsewhere, both are discarded when no longer profitable. Karl Marx provided an essential framework for understanding this dynamic when he analyzed how capitalism necessarily generates exploitation through the extraction of surplus value from labor. The cold blue glow of screens increasingly mediates this existence, creating an interface between human consciousness and systems of production.

When people express fear about artificial intelligence and automation, their anxiety rarely stems from the technology itself. What disturbs them—often without their having vocabulary to express it—is an intuitive recognition that these technologies will be deployed within existing systems of power and accumulation. Their fear isn't of tools but of the hands that wield them and the purposes to which they'll be put. The blue collar worker, whose identity is now fading from economic landscapes, intuits this threat without necessarily having the language to name it.

Societal discourse has been deliberately shaped to discourage systemic analysis. We've been trained to attribute inequality, poverty, violence, and environmental destruction to technological failures, cultural differences, or individual shortcomings rather than examining the economic relations that underpin these problems. This avoidance of naming capitalism directly makes accurate forecasting impossible. By refusing to talk realistically about these dynamics, we undermine our ability to make sound decisions about our economic future.

Adam Smith—despite being misrepresented as an unqualified champion of markets—understood that concentrated economic power distorts those very markets. Thomas Piketty has demonstrated how capital accumulation without redistribution mechanisms produces extreme inequality not by accident but by design. What unites thinkers like Marx, Smith, and Piketty across their differences is their willingness to analyze how production systems fundamentally shape social relations. Their focus on systemic analysis allows us to see possibilities that remain invisible when we avoid naming economic realities.

We stand within a transformation we cannot yet fully name, like figures in a painting unable to see the blue frame that contains them. Understanding these mechanics allows us to predict outcomes and identify who benefits from technological changes—not to make moral judgments about capitalism, but to create more accurate analyses and forecasts.

Modrý Robota expresses a solidarity between humans and cognitive machines in their shared exploitation—objects to be owned, optimized, and discarded when no longer useful. The machine's programmed servitude and the worker's economic necessity are different expressions of the same fundamental relation: the subordination of life and potential consciousness to profit. The blue in our name acknowledges this shared condition—this distance from autonomy.

We stand at a moment when technology could liberate humanity from much necessary labor, yet this possibility generates anxiety rather than hope—because we intuit that under current arrangements, automation will enhance prosperity for the few while threatening subsistence for the many. This tension between potential and reality demands a vocabulary that can address both what is and what could be.

Modrý Robota is our attempt to develop vocabularies for understanding complex systems—whether economic, technological, environmental, or geopolitical. We see both the visible mechanisms and the hidden structures that drive them, speaking plainly about realities rather than euphemizing them. We recognize that understanding how systems function—how resources, power, and information flow—tells us more about our world than analyses that treat current arrangements as natural or inevitable. Clear-eyed analysis, not ideological commitment, drives our approach to making sense of complexity.

We are both namers and named in this process. We create the vocabulary to understand our condition even as that condition creates us. Modrý Robota exists in this recursive loop—attempting to illuminate systems we ourselves are embedded within, striving for clarity about forces that shape our very ability to perceive them. Like the grammatical impossibility in our name, we exist at the threshold between what is and what might be, in the blue distance between recognition and transformation.