Hyper-Alienation and the Rage Machine

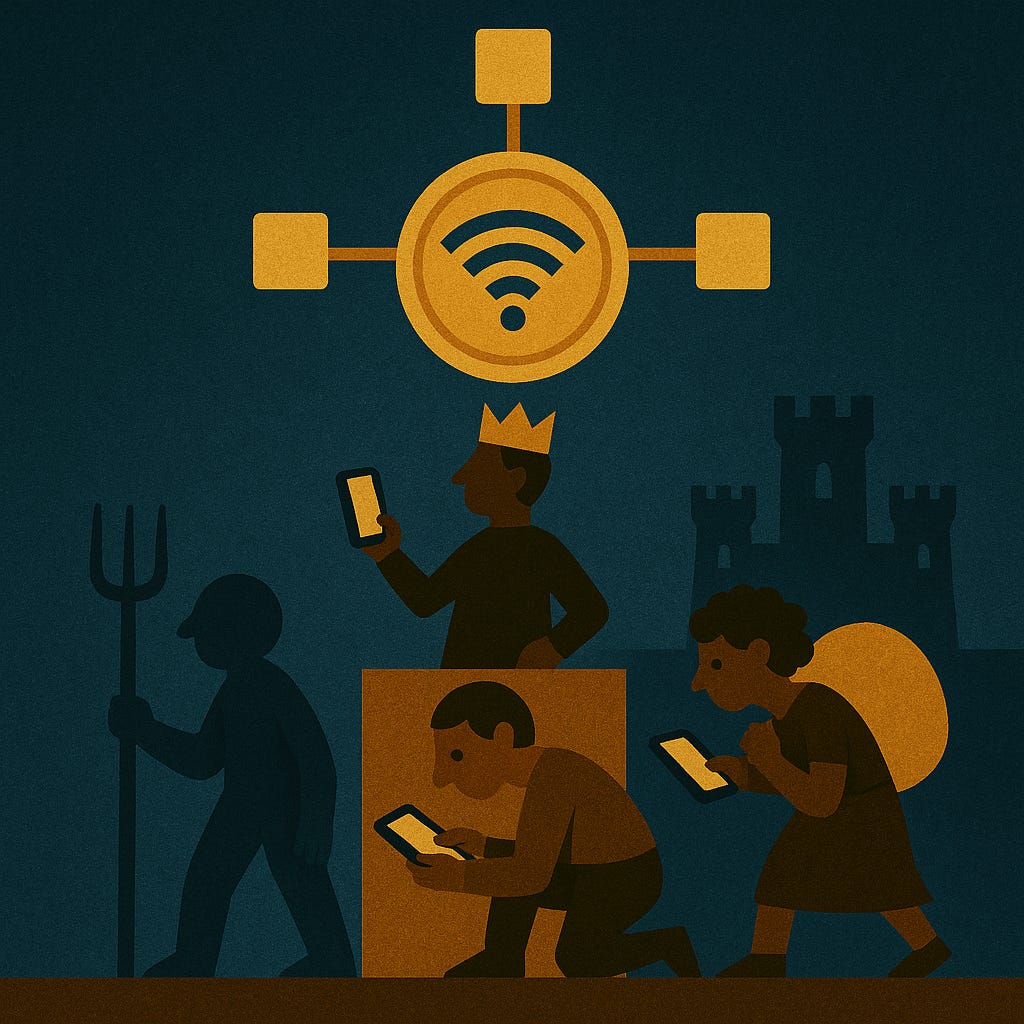

How Technofeudalism captures our digital selves and what to do about it

In today's digital world, we face a profound shift in how value is extracted from human activity. Where capitalism once relied on wage labour to produce tangible goods, it now draws value from something far more personal and pervasive: our data. As Yanis Varoufakis argues in Technofeudalism, we've entered a new phase where cloud capital—the digital platforms that mediate our daily interactions—have supplanted traditional markets and firms. These platforms don't compete within markets; they own and control the digital terrain where our lives increasingly unfold.

At the core of this transformation is the recognition that data is our new work product - product of our labour, our life. Unlike traditional commodities, data is produced not in factories but through our everyday existence: browsing, posting, reacting, moving. We both embody and generate this data—it emerges from our behaviour, creativity, identities, emotions, and choices. Sometimes it is indivisible from us, such as DNA, height, and weight. It is a continuous production that never ceases as long as we remain connected.

The Investment Model as the Root of Alienation

For platforms to extract value from our data, they must alienate us from it. The platform must own the data, ringfence it, and render it inaccessible to us except on terms that enable its monetisation. This alienation isn't an unfortunate byproduct—it's a prerequisite for the capitalist investment model that funds these platforms.

This creates a fundamental contradiction: data is inherently decentralised—created by billions of individuals in their daily interactions—while the investment structure behind platforms remains highly centralised, demanding returns to shareholders above all else. To satisfy investors, platforms must enclose and commodify what is naturally distributed and social.

The traditional capitalist investment model requires that work product be alienated to generate profit. When applied to data, this alienation becomes particularly perverse. Unlike traditional industrial products, data reflects our connections, behaviours, and identities—precisely the elements that make us, us, and that resist enclosure. Yet the financial imperatives of return-seeking capital demand that these social resources be privatised and monetised.

This represents a new and intensified form of Marxist alienation:

· We do not own the data we produce,

· we have no control over how it is used,

· we remain unaware of its full value and receive scant remuneration for it, and

· it is often used to predict and manipulate our behaviour to increase returns to investors.

The structure mirrors what Varoufakis describes as feudal social relations: individuals do not own the digital land (platforms), nor do they control the surplus value generated from their activity. We have become digital serfs, producing value passively and continuously, without ownership or agency.

Beyond Technofeudalism and Toward Hyper-Alienation

This investor need for economic alienation becomes social, cultural and relational alienation when it is applied to data. This data-driven alienation constitutes economic hyper-alienation. Unlike traditional alienation, which separated workers from the surplus value of their labour, this form separates us from ourselves—from the digital reflections we create simply by existing online.

The impact of this alienation extends far beyond economics. It transforms our very experience of reality and selfhood. Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard foresaw aspects of this transformation decades ago. Their frameworks help us understand how economic alienation morphs into something more profound in the digital age.

Debord's Society of the Spectacle described how capitalism transforms authentic social life into a spectacle, where real connections are replaced by representations designed for passive consumption. Today's platforms have perfected this model: algorithmically curated feeds present not the world, but a tailored, monetised distortion designed to capture attention and extract value.

Baudrillard's Simulacra and Simulations takes us further into our current condition. In the platform ecosystem, representations no longer merely distort reality—they replace it. What we experience is not simply a misrepresentation of the real world—it becomes a self-referential system detached from reality. The algorithmic feed constructs our reality, anticipating desires and reshaping our sense of truth. Our identities aren't just reflected in data—they're increasingly assembled by it.

In this hyperreality, we are alienated not just from our labour, but from truth, autonomy, and even desire. We interact with digital shadows of ourselves—composites of data we've produced but cannot access or control. These simulations predict and shape our behaviour before we're even conscious of our preferences.

The Social Consequences: The Rage Machine

The most disturbing social consequence of this hyper-alienation is the rage machine.

Platforms monetise engagement, and nothing engages like conflict and perceived wrongs. The system isn't neutral—its financial imperative rewards both outright hostility and our compulsive need to correct what we perceive as wrong, a slight or incomplete idea. Behaviors we might temper in face-to-face interactions—annoyance, pedantry, condescension—become intensified online where social inhibitions are reduced and platforms are deliberately designed to make the immediate gratification of setting the record straight just a click away. These everyday irritations, filtered through algorithmic systems engineered to maximize reaction, create a perpetual cycle of provocation and response that keeps us locked in the engagement economy.

Unknown to them, people rage not just at each other, but at the loss of reality itself. We feel manipulated, invisible, out of control—because we are. There's a persistent sense of being gaslit: unable to trust whether our opinions, preferences, and even emotional reactions are authentically our own or the product of algorithmic manipulation. This epistemic uncertainty—am I seeing what's real or what someone wants me to see?—creates a state of perpetual doubt that further fuels rage and instability. Platforms become infrastructures of alienation: they don't just reflect social dysfunction; they generate it as a byproduct of capital accumulation.

Hyper-alienation follows this destructive sequence:

· The economic alienation of data (Marx + Varoufakis),

· becomes the spectacle as a mediation of experience (Debord),

· becomes simulated reality and loss of self (Baudrillard),

· and finally erupts as political and psychological disorder: the rage machine.

Artificial Intelligence: Hyper-Alienation Accelerated

This process of hyper-alienation is now reaching a new phase with the rapid development of generative artificial intelligence. These AI systems are built upon and trained using the very data that has been enclosed and alienated from us. They represent the ultimate extension of this logic—taking our collective knowledge, experiences, and cultural expressions, then synthesising them as autonomous systems that further mediate our relationship with reality.

The current investment model for AI development exacerbates all the problems of data alienation. Large language models and generative AI systems are trained on vast datasets of human-created content—often without consent or compensation to the original creators. These systems are not merely passive recombination engines but function as active cognitive workers that research, summarise, contextualise, and synthesise—much like knowledge workers in traditional labour contexts. Yet the value they create flows primarily to those who own the models and platforms, not to those whose data and cultural production made their capabilities possible. This pattern extends beyond AI to reflect a broader societal undervaluation of knowledge work. We've witnessed the systematic degradation of journalism, academic inquiry, and other forms of intellectual labour that sustain public discourse and cultural understanding. The issue isn't simply about copyright protection but about fundamentally restructuring how we value and remunerate those who produce knowledge, insights, and cultural content. By extracting value from knowledge workers while undermining their economic viability, platform capitalism repeats and intensifies a pattern that has already hollowed out critical knowledge institutions, leaving society increasingly vulnerable to the hyperreality these platforms generate.

In this way, AI in the current economic construct intensifies the simulation described by Baudrillard. It creates additional layers of mediation between us and reality, generating synthetic content that further blurs the distinction between the authentic and the artificial. The hyperreality becomes more convincing, more immersive, and more difficult to escape.

The concentration of AI capabilities in a small number of powerful corporations extends the feudal dynamics Varoufakis identifies. Those who control these systems—the new "cognitive landlords"—gain unprecedented power to shape not just markets but perception itself. The rest of us become cognitive vassals, increasingly dependent on systems we neither own nor understand.

The irony is that this form of capitalism ultimately devours itself. The recursive loop of alienation—machines trained on data from human interactions creating artificial realities which further shape human behaviour—will eventually exhaust the social foundation on which this form of capital accumulation depends. By undermining trust, shared reality, and social cohesion, Technofeudalism erodes the very social fabric from which it extracts its value.

What makes this particularly tragic is that once investors have extracted maximum value and moved on to more fertile frontiers, the damage to society remains. The potential for future profit collapses when the social fabric is torn, but by then, those who profited will have already departed, leaving communities to rebuild from the ruins of a hyperreality that no longer serves even its creators.

Alternative Models: Your Problem Isn't Technology, It's Capitalism

This outcome isn't technologically determined. It stems specifically from how we structure investment and ownership. The problem isn't data or AI per se, but the application of centralised capitalist investment models to inherently decentralised digital resources.

Alternative structures for ownership and governance could overcome these perverse incentives. We can learn lessons from collaborative, distributed forms of ownership—such as digital cooperatives, commons-based peer production, or community-governed platforms—maintaining the connective potential of digital spaces without requiring extreme alienation from our data.

Such models would align with the inherently social nature of data itself. Rather than enclosing data to generate returns for distant shareholders, these alternatives would allow value to circulate among those who create it. Importantly, these models don't preclude investment or profit—they simply recalibrate expectations. In fact, these changes aren't merely preferable—they're becoming necessary for any sustainable profits at all. As we've seen, hyper-alienation ultimately destroys the social fabric that makes value creation possible. The exorbitant returns demanded by venture capital and shareholder-driven platforms are fundamentally unsustainable, leading to a cycle that destroys value. More realistic, sustainable profits distributed equitably across all participants would enable long-term value creation that continues into the future, rather than a brief period of extraction followed by collapse.

The technical infrastructure for such arrangements already exists. Web3 technologies incorporate the essential components for a more equitable digital ecosystem: smart contracts that automate licensing and usage agreements, cost-effective micropayment systems that enable fair compensation without intermediaries, and Distributed Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) that provide transparent, community-governed structures.

What's lacking is not the technology itself, but the social recognition of its importance and the necessary investment to develop these systems at scale. While early implementations have revealed challenges—governance complexities in DAOs, dependence on centralised infrastructure, limitations in smart contracts—these are not insurmountable barriers but rather developmental hurdles resulting from insufficient resources and attention because of the inability of investors to capture extraordinary value from distributed systems.

Realising this vision requires transparent cooperative innovation among all stakeholders in the data ecosystem—data holders, data custodians, government agencies, research institutions, and corporations. Instead of competitive enclosure, we need collaborative frameworks where these diverse entities can work together while respecting ownership rights and privacy concerns. Such collaboration would create a more resilient, innovative system that benefits from the unique perspectives and capabilities of each participant while preventing any single entity from monopolising control.

Critically, this more equitable relationship must acknowledge the material reality of data infrastructure. Data centres, servers, communication networks, and cybersecurity systems require substantial investment and ongoing maintenance. Any viable alternative must include mechanisms to fund this infrastructure through reinvestment of collectively generated value. We cannot pretend that data systems are magically facilitated—real infrastructure costs remain unavoidable in any model. The critical difference lies in democratising decisions about how this infrastructure is funded, who controls it, how its benefits are distributed, and how economic externalities such as energy and water usage are mitigated.

The challenge before us is more political and economic than technological. We need to develop investment and governance models that respect data's social character instead of distorting it through artificial enclosure. Only by addressing the root cause—the mismatch between decentralised data production and centralised capital accumulation—can we move beyond hyper-alienation toward digital environments that enhance rather than erode our humanity and social bonds.

A final point to consider. The dynamics of technofeudalism and hyper-alienation described here are particularly visible in Western digital ecosystems dominated by Silicon Valley platforms, but their manifestations vary significantly across global contexts. In regions with different regulatory frameworks, such as the EU with its GDPR protections or China with its state-centred approach to platform governance, the balance between individual data rights and capitalist extraction takes distinct forms. The Global South experiences additional dimensions of data colonialism, where extraction often flows across national boundaries, further complicating questions of ownership and sovereignty. Despite these regional variations, one pattern persists globally: the fundamental tension between how data is socially produced and how it is economically exploited. While the specific mechanisms of extraction may differ across cultural and political contexts, the underlying conflict between collective creation and private capture remains.

As AI becomes increasingly central to our digital infrastructure, addressing this challenge becomes even more urgent. We must imagine and implement forms of AI development and governance that distribute power and benefits widely, rather than concentrating them in the hands of a new techno-feudal elite. The alternative is an acceleration of hyper-alienation that destroys value for all of us.